Government Amends IT Rules, Imposes New Requirements on Social Media

03 Nov 2022

The Centre notified changes to the existing IT Rules for online platforms operating in India. An grievance appellate committee will handle user complaints, with social media, entertainment sites, apps, and other tech companies mandated to comply.

Grievance Appellate Committee to Deter Social Media Abuse

When the Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code (known as IT Rules) were amended last year, all online “intermediaries” and social media were cautioned and expected to comply duly. Now, the IT Rules have been updated, and the Centre is admonishing major tech players for their overall inactivity. As a result, more monitoring and review functions will be taken by Indian authorities.

Effective immediately, the IT Amendment Rules (2022) have been published by the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY). And although they are still gathering feedback on some points, the government has given the green light for the creation of a Grievance Appellate Committee (GAC).

The GAC will be established within three months and will handle user grievances and content moderation decisions – possibly reversing some – of tech giants like Facebook (Meta), YouTube (Google), and Twitter. Users may approach the Committee within 30 days after an event and expect a response within a month as well.

The amended Rules also require platforms to inform and remind users of relevant policies and existing agreements at least once per year. Changes to those should be notified timely, and complaints acknowledged within 24 hours (with a resolution within 15 days).

IT Rules Empower Citizens to Signal Mistreatment, Illegal Use of Social Media

At first glance, many of the reasons to raise a complaint are covered by existing laws. However, the new IT Rules make government requirements from social media more explicit, particularly by making “reasonable efforts” to avoid hosting or handling illegal or harmful information.

In particular, the GAC will review suspected cases of ID theft, invasion of privacy, discrimination, harassment, pornography, incitement to violence, or threats to minors. The Committee is also expected to deal with IP rights infringement, money laundering, and even illegal gambling accounts.

However, the GAC will be able to judge on suspected threats to security and public order, including misleading information of any kind. The Rules also open the possibility of addressing issues that infringe on any other laws in force.

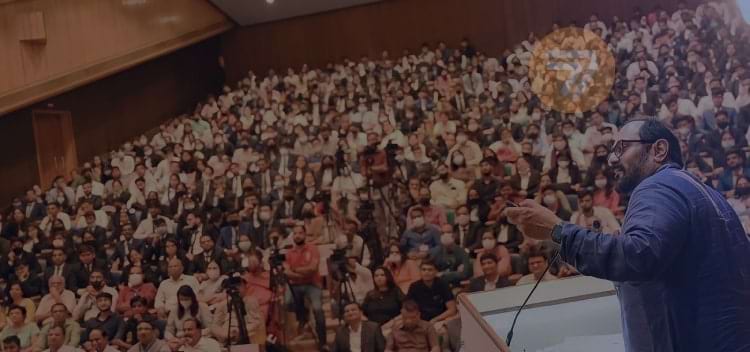

The Minister of State for Skill Development and Entrepreneurship and Electronics and Information Technology, Rajeev Chandrasekhar, explained a couple of days later that the Amendments would make it harder for social media to suspend accounts arbitrarily just as much as hosting harmful content. Above all, he said the Rules were laying the basis for a more systematic process of reviewing online activity.

The Grievance Appellate Committee was set up after online platforms had done little since last year’s Amendments. Above all, the previously required Grievances Officer had turned out to be a letterbox figure in most cases. The Centre took matters into its own hands, with the Minister citing an understanding of “natural justice” as justification for the new setup.

Still No Common Framework on Rules for Online Pastimes

Undeniably, over the past few months, we have seen a gradual roll-out of responsible usage policies in big tech, gaming, and entertainment platforms. More than anything, it has been an uncoordinated mixture of self-regulation and government-imposed requirements.

Apple recently blocked iPhones from displaying gambling ads on its Apps Store. Earlier last month, Instagram introduced four methods of age verification for user accounts, much like legal gambling platforms approach the matter. And over several months, the Centre issued an advisory to TV and OTT platforms – twice – against allowing illegal betting ads.

These all seem like necessary steps to protect vulnerable users and especially minors, albeit without a broader systematic policy for most issues. Then the government decides unilaterally on such ad hoc rules; the measures are often without market logic. Most importantly, authorities lack the technical capacity to monitor and enforce such expectations, making them instantly obsolete without the contribution of the tech industry and consumer groups.