Online Gambling in Goa on the Rise

While land- and river-based casinos in Goa are the true symbol of the small coastal state, online platforms have been the talk of the gaming industry for the past few years. Online casinos have also left their mark in Goa, just as they have across the rest of India. Local gambling communities are looking for safe and accessible platforms, particularly after recent experiences with lockdowns and proposed entry bans on Goans (see more below).

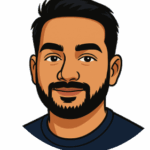

We have analysed aggregate SevenJackpots data for six months of user visits – including conversion rates and user experience (UX) in terms of device and session indicators. Segmented by state, the figures show that Goa has more than double the proportional visibility (0.23%) compared to its population size of just 1.5 million (0.1% of the Union).

This is partly because of its economic development, yet Goa’s standing has historically been boosted by the rewarding effects of its gambling tourism. Nevertheless, the fact that it accounts for more online casino players than all of the North-Eastern states of Meghalaya, Tripura, Mizoram, Nagaland, and Arunachal Pradesh – combined – is simply impressive. Goans are clearly actively looking for online alternatives to said limitations.

How Much Tax Revenue Does Goa Make from Casinos?

Pragmatically speaking, the potential impact on public finances is always a decisive factor among the key reasons to regulate the gambling market. Goa authorities may aspire to see a more transparent and innovative gambling environment, with even less money laundering and corruption. However, the effects that regulated gambling has had on the local business climate and job creation have always been easy to illustrate.

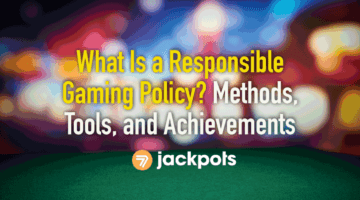

In FY 2012-2013, these public spillovers were still limited, contributing an estimated Rs 135.45 crore in direct taxes, entry fees, port charges, and liquor licences, among other revenues. Goa charged a reported Rs 6.5 crore annually per offshore and Rs 2.5 crore per land-based casino at the time.

By FY2018, the state received Rs 330 crore from the casino industry. A year later, the direct tax revenues alone were already at Rs 411 crore, the highest pre-pandemic figure to date.

Tax Revenue

Under normal conditions, Goa boasts three million tourists annually and around 15 thousand gamblers daily in peak season. With proper industry support, the state exchequer could probably see a further increase in the above figures. Currently, offshore casinos are said to bring almost twice the revenue compared to land-based facilities, mostly due to the specific tourist flow to these vessels.

Despite that, media reports cite losses of over Rs 4,000 crore in annual tax revenue, mostly because of undeclared cash gaming. Most casino operations are strictly a cash affair, a phenomenon that is strategically opposite to the national vision of a cashless economy.

Goa’s gambling scene has built a reputation over the years. Its mass-market appeal is not a shortcoming; quite the contrary – it allows the state and private gaming operators to pursue alternative business models and platforms. They could do much more to capitalise on particular fame through various channels.

Below, we have provided a brief overview of what India could achieve in terms of public revenues if only states like Goa decide to open up to nationwide online gambling. Our dedicated study on Indian gambling regulation explains the figures in more detail.

Land-Based and Riverboat Casinos – Goan Pride and Financial Pillar

Even without taking into account the possibility of regulated online gambling, Goa remains one of the few states in India where both brick-and-mortar and floating casinos are legal. Visitors from near and far come to enjoy the beaches, but most combine it with the chance to indulge in real-money gaming.

The classy gambling venues and casino cruises represent an old-fashioned competition to today’s online casinos. In an earlier editorial review, we looked at the most popular casino ships around Goa – like the Majestic Pride Casino, the Deltin Jaqk, Big Daddy Casino, and Casino Pride. Most are located along the Mandovi River or in the bay across from the capital Panaji.

The floating casinos offer all the game-floor classics, slots, and table games, many of which are assisted by live dealers. Most of the vessels offer luxurious gaming experiences, including bars, restaurants, and hotel rooms on board.

Land-based Casinos

There are also a number of land-based casinos around the state of Goa. The most prominent are the Deltin Royale, the Casino Carnival, and the Deltin Zuri. Typically, the onshore gaming halls are located within resorts and hotels and are often surrounded by pools, spa centres, restaurants, and bars. They frequently host dance performances, live musicians, and disco nights with celebrity appearances.

Altogether, there are six offshore casinos and about a dozen land-based ones. These have varied slightly in numbers for the past decade, with operators gradually moving some of the floating casinos within five-star hotels. The market leader is Delta Corp, the only listed Indian gambling company which runs the Deltin brand. Other notable players include the Pride Group and the Advani group. All of these businesses also operate the hotels hosting the casinos.

Industry experts and politicians have noted that the transition to holiday-centred gambling trips has been natural for most desi players. The Indian passion for gambling is openly observed at festival times, with a rich choice of legal and illegal gambling options. While gambling behind closed doors is a public secret, festival gambling is no secret at all. In fact, Goa’s Tourism and Chief Ministers have previously pointed to festival (“zatra”) gambling as a pre-existing tradition that justifies the government’s formal and informal support for the local operators.

A Crucial Source of Tourism

In light of this, one question remains – between gambling and tourism, which is the primary and secondary revenue source for Goa? As a “package” entertainment destination, the state offers a range of pastimes and gaming options, from small floating casinos to large resorts with hundreds of gaming tables and thousands of slot machines.

Although a leisure destination since the 1960s, Goa added gambling to its tourist brand some thirty years later. Casinos were initially seen as a necessary catalyst for economic growth, particularly after the state began receiving mining bans from various courts. Iron ore mining had been a crucial driver of the Goan economy for five decades until 2012.

Liberalisation did not come with the Goa, Daman and Diu Public Gaming Act of 1976 but when the first gambling licences to luxury hotels were launched in 1992. Table games like roulette and poker were allowed in 1996, initially only on cruise ship casinos. The latter policy made gambling operators seek an offshore presence in Goa.

Nowadays, tourism accounts for 30% of state GDP, but casinos are the true cash cow behind that. Desi players around the Union recognise Goa as a viable alternative to illegal local gambling markets. For those who can afford the trip, regulated gambling is always preferred.

Inclusivity

Being flexible and family-friendly is in growing demand by casino players arriving in Goa. Currently, most operators invest in integrated casinos and entertainment centres as part of a more inclusive kind of tourism. Local Government plans envision setting up several enclosed complex hotels along with convention centres, cinemas, retail areas, water parks, and casinos near the new MOPA airport in North Goa.

Even though residents think casinos could be better run and regulated as an industry, they know that the segment has always stood behind and boosted Goa tourism. A glamorous yet affordable experience, Goa promotes gaming as fun and exciting, an oasis of legal real-money pastimes.

Nowadays, offshore vessels and integrated resorts tend to transition towards family entertainment, akin to the universal appeal of Vegas. In line with this “image makeover,” many have even opened daycare centres and regularly hold non-gambling-related entertainment events (concerts, stand-up shows, dancers, and much more).

Goa Gamblers’ Profile

Scientific studies have shown that at least half of all Goans have gambled at least once in their lives, with 45.4% in the past year alone. Interestingly, 40% of players are fans of old-fashioned Satta Matka games (and their derivatives), despite those being illegal and the presence of many legal gaming parlours. Unsurprisingly, 45% of all men in Goa identify themselves as gamblers.

Unlike Macao, which caters to high rollers, Goa has opted for a broader market and being more accessible. The chairman of Delta Corp once revealed that the average player value is between $200 and $300. Only about a fifth of all visitors is reported as hard-core players.

Roulette and blackjack are the most popular games, albeit distinctly Western. Local casinos compete for tourist gamblers who might have gone to Macao before but are happy to visit Goa for a more affordable getaway.

Who Plays in Goa?

Some casinos hire Bollywood ambassadors to promote their brand, positioning gambling tourism as the “thrill, glitz, and glamour” kind of lifestyle. For obvious reasons, safety and health standards are the latest additions to the list.

On the other hand, the above research also reveals that lottery is the most frequent form of real-money gaming and the choice of 67.8% of Goa’s active players, particularly older ones. People tend to remain loyal to one type of game, with only a third playing 2-3 (or more) games regularly. This is just as much an Indian tradition as it is the case in mature markets like the US, the UK, and Europe.

In the end, casinos in Goa are not as popular among locals, possibly since games of chance are also found elsewhere. Casinos are rather seen as entertainment venues, as we noted earlier. Still, locals outnumber tourists on land (between 50% and 80%), while offshore casinos welcome mostly tourists (70%, as per 2014 estimates).

Structural Challenges and Local Opposition

Among Goans who do not frequent casinos, we also see a group who oppose them. Some perceive the industry as the source of river pollution and congestion, and others fear potential socio-economic collateral effects that make the state a “sin-tourism” destination.

While purification and waste disposal standards can counter environmental concerns, locals also talk about a potential rise in crime. However, Goa’s CM confirmed that crime rates had fallen between 2014 and 2017 and had no direct relation to casinos.

Concerns about mental health, problem gaming, and related addictions are also notable. Limited studies are done locally, but there is plenty on record in other Asian jurisdictions with long gambling traditions.

A 2015 study registered a slight increase in problem gambling in Macao registered a slight rise between 2003 and 2007 (4.3% to 6%), the period immediately after the administration opened up the casino industry to foreign investors.

However, similar transition periods in Singapore and Hong Kong have gone without the slightest rise in problem gaming. According to the Institute for the Study of Commercial Gaming (ibid), both registered a decrease in problem gamblers – Hong Kong went from 5.9% to 4.5% (between 2001 and 2008), and Singapore from 4.4% to 2.9% (2004–2008).

Conservative and populist politicians in Goa take advantage of opposition sentiments. Yet, they try not to criticise the Goa lifestyle openly, as it remains a potent vehicle for advertising the state as an affordable glamor spot where money games are legal, and people’s passions are welcome.

Challenges and Regulation

When the state Chief Minister proposed banning locals from entering casinos, many realised the motion would fail since most casino staff, and many of the visitors are Goans. A decade after the first proposal (2012), no rules and monitoring mechanism has been set up, and operators have challenges in various courts.

Goa residents and politicians recognise the importance of planning ahead to face existing challenges. Coming up with a sustainable long-term strategy would require maximising gains yet counteracting negative collaterals. But calls to revert Panjim to its pre-1990 state (or even bring back the 1960s) are as meaningless as they are unrealistic.

Goa’s gambling appeal has already seen it dubbed a casino capital of South Asia. Uncertainty in casino hubs like Kathmandu and higher client demands in Macao play in Goa’s favor. Local authorities must work together with businesses to reinvest public revenues and plan for positive spillover effects.

With Las Vegas as mass-market inspiration, it is easy to prove that efficiency is best achieved through better regulation, including against any undesirable social impacts. Pursuing the family entertainment appeal we quoted above also allows businesses to plan more transparently and to act and advertise more responsibly.

Can Goa Scale Up? The Potential of Nationwide Operations

Casinos in Goa are already a solid and profitable reality. Yet, considering the global digital transition for the better part of the past decade. It is time to look at a potential shift to online operations. Unlimited in capacity, safe, and always open.

At first, this will allow Goa to tap into the entire Union market while still operating under state law. While a 2021 Deloitte India report placed online gaming in India at $2.8 billion (₹22,500 crores at current exchange rates), the 2019 KPMG report estimated the total desi betting market at $130 billion (~Rs 10 lakh crore).

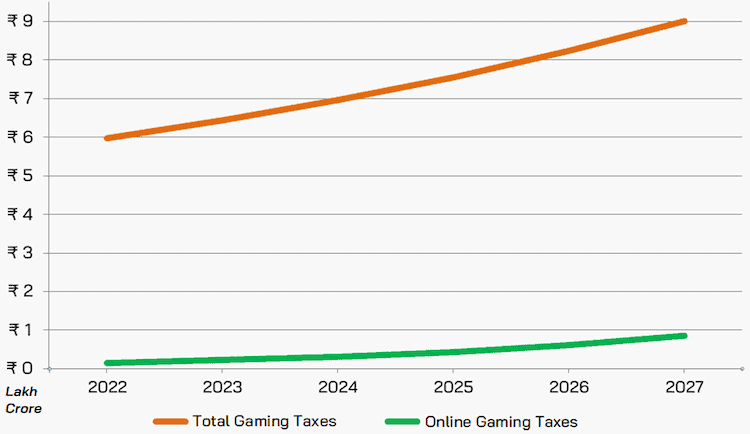

Projecting the current industry growth levels further, we have calculated that by 2025-2026 India’s real-money gaming market could contribute astounding amounts of tax revenues alone – if only the market were to be fully and effectively regulated.

Projected annual tax revenues of around Rs 9 lakh crore could finance the public sector, create jobs, and build schools and hospitals. Similar levels of public funding can produce spillover benefits from the digital sector into land-based economic development (one such use was proposed for the Centre’s 100 lakh crore “Gatishakti” infrastructure plan).

When the pandemic hit Goa’s casino and hospitality industry, old-fashioned gambling started looking less competitive than ever. Legal online alternatives boosted a demand pattern that was simply not there several years earlier.

Although Goa’s casino brand may have the potential to exploit global levels of its fame, getting remote access to India’s Union market looks like the least logical step. That is, until other states recognise it is in their best interest to regulate their own domestic real-money gaming markets.

Gambling Regulation Done Well

Due to its small territory and gambling traditions, Goa makes for the perfect case study for regulatory changes – i.e., the ability of local authorities to pass and implement rules, their efficiency, and resulting impacts. Goa is also a reference point for a state that allows both government lotteries and licensed casino games, and notably, lotteries are state-run, while casinos are always private.

Liberalisation was passed initially through licences for luxury hotels. When land-based casinos started transforming the economy (and society), cruise ship casinos got their chance to host gamblers on the Mandovi river. The systematic promotion resulted in the mass-market appeal at national levels, adding games, locations, and facilities. In 2006, Goa finally set up its state lottery to promote social welfare through its proceeds.

The importance of regulated revenue sources was undeniable at that point. The government justified casino operations as a generator for tourism, publicly backing the industry as the largest employer in Goa.

University research has shown that Macao followed a similar trajectory after 1999. But only opening up to foreign operators (three years later) brought the needed competitive edge, entrepreneurial culture, and modern facilities. In 2006, Macao surpassed Las Vegas as the world’s largest gambling centre.

Online Casino Competition Is Growing

Although Sikkim and Daman also allow games of chance, casinos have been a Goan trademark for over three decades. However, they risk losing their special status after online gaming has emerged. As a mainstream option for over 400 million desi players.

Meghalaya adopted a new Gambling Act in 2021, projecting the issue of licenses to companies based anywhere in India. Rajasthan also presented its Virtual Online Sports (Regulation) Bill in 2022. In an attempt to regulate pay-to-play “virtual online sports” – esports, fantasy leagues, and “derived formats.” In 2016, Nagaland formally regulated online poker along with other skill games for money.

Among these, Meghalaya has acted the quickest, fully and officially legalising gambling. The Meghalaya Regulation of Gaming Act was passed in March of 2021. And by December, its legislators had set up detailed rules for implementation. The Meghalaya Gaming Commission is also India’s first properly constituted state regulator.

Online gambling is not only a direct competitor for Goa casinos. In today’s mobile-first entertainment market, it might just be too much for an exclusively land-based gaming industry.

The Clear Benefits of Online Transition

We have written about this before. A transparent and traceable online gambling environment has immediate financial impacts, particularly against money laundering and corruption. A regulated online gambling industry also improves job creation and the business climate. Quite importantly, digital platforms have the means to promote responsible gaming.

Many of the perceived shortcomings of Goa’s gambling scene could find solutions in better regulated online environments.

- Goa youth can receive training and keep the jobs that the industry currently provides;

- Floating casinos will get a sensible transition roadmap. While digital gaming will allow land-based venues to focus on wider-range entertainment activities;

- Problem gaming will get the funds, support programs, and safety nets that produce tangible results in the long run;

- Public financial interests will be protected through agencies and monitoring mechanisms that can preserve competition, innovation, and growth.

Goa was a trailblazer in the early 2000s, but now it could end up trailing its national and global competitors. Its regulatory authority (Commission) has been in the works for several years, delayed repeatedly by government officials. Combining on-site regulation and ambitious digitisation efforts can help the industry meet modern market demands.

Conclusion: Looking Back or Moving On

For the time being, Goa casinos remain a poster example of legal gambling in India. They still have considerable appeal to the nation’s growing middle class, pulling in tourists with their striking image.

However, staying afloat requires sustainable planning and investment, attracting more quality operators and staff, and raising standards for existing ones. The Goa government must also carry out awareness campaigns and better inform locals about industry plans and responsibilities. Put simply; it needs to educate both companies and gamblers and welcome those that know how to act responsibly.

An online expansion will not hurt Goa’s existing tourism and entertainment industries. It will only give them viable alternatives and business models that will have them reap benefits in the long run. Next-generation users might not seem an appealing market at first. But they are the future and a much more sizeable market than a handful of high-roller gamblers during festival season.

Ultimately, online casino operations can help the already rich state of Goa stay ahead of other jurisdictions that fail to comprehend the importance of regulation and digitisation.